Our Need for Net Neutrality: Is Democracy Threatened?

December 21, 2017

The year is 2025, and you’d like to watch some YouTube on your desktop. You bought a pretty good internet access package from Comcast, so the use of Google subsidiaries is included in the contract, but you don’t like that the monthly bill is so expensive. Sometimes you wish you could use Netflix again on this package, but, like they did in 2014, Comcast throttled its speed down when Netflix refused to pay premiums. It’d be nice to catch up with those awesome Netflix original series, but you guess it’s okay, you’ve still got Hulu. For now.

Advertisements have gotten worse lately, too. As you click into YouTube you see an unskippable thirty-second ad on the video you’re about to watch. And there are two more behind it.

The video complete, you close out of YouTube and cruise over to your Internet Service Provider’s (ISP) website to do your monthly internet bill. Maybe for some extra money you could buy Netflix access as an add-on. If your access package provider will allow it.

Since it has recently been repealed by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), there are some facts you might want to know about net neutrality. According to FreePress’ Save The Internet campaign, it means “an internet that enables and protects free speech. It means that ISPs should provide us with open networks — and shouldn’t block or discriminate against any applications or content that ride over those networks.”

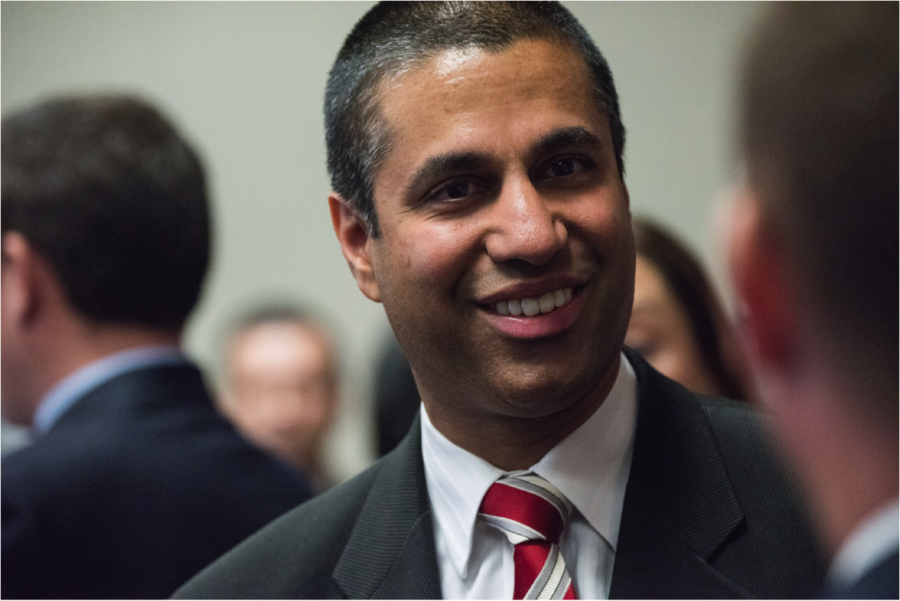

According to Ajit Pai, the head of the FCC who lead the charge in eliminating it, the rule establishes the World Wide Web as a “government-run operation” that “put[s] the government rather than the private sector at the center of how the Internet operates.”

But, whether or not it is correct to get rid of net neutrality wholly depends on how the Internet is defined: a globally available tool of free speech or a free-market commodity. Instead of getting caught up in the semantics of how the Internet is defined, let’s consider whether net neutrality is good for the consumer.

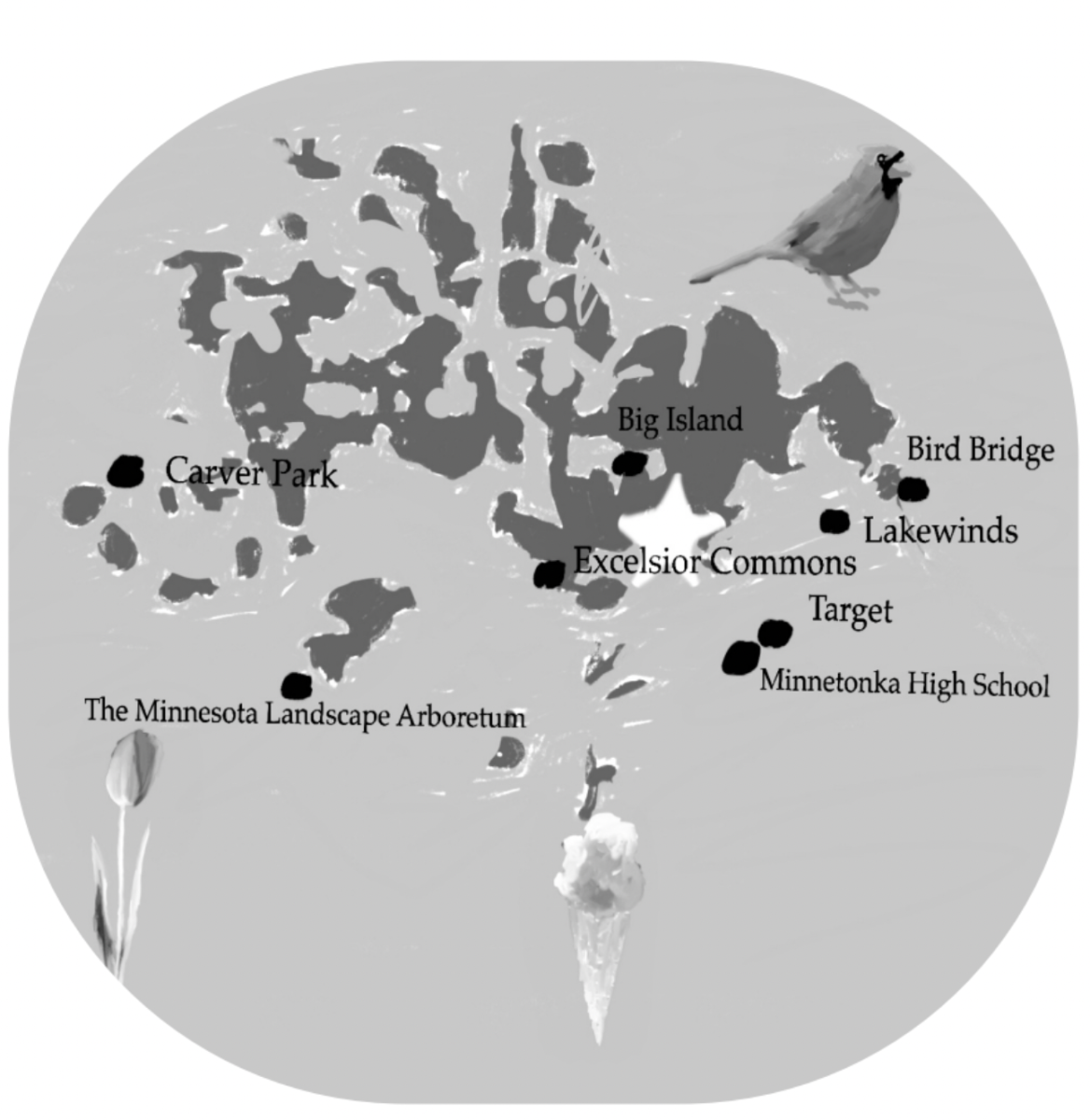

I asked this question of Mr. Bahr, a computer science teacher at Minnetonka High.

As a teacher of the principle functions that make up computer programs, he believes that “if we give control back to the ISPs, it will have a negative impact on consumers and only put more money back in the pockets of the corporations…it looks like another win for the corporations, but not the actual customers who use the service.”

He also pointed out a problem with the large ISPs that own multiple companies, saying that “The conflict of interest is clear to see. Comcast owns Hulu. Who is a direct competitor of Hulu? Netflix. Once Comcast is able to slow down or charge more for the use of Netflix on their networks, it’s only a matter of time before [it] happens.”

I also interviewed Ina Koivisto, a self-described broke college student who relies on unfiltered Internet content heavily for school.

“All of my classes use various websites to give us materials for class and record for our grades,” she said. Without net neutrality, “communications with my professors and classmates would be limited; I’d have less access to materials I need, and I would have a harder time studying for exams.”

She also added, “[I‘m] broke from overpriced tuition. Please don’t make me pay for internet.”

The FCC’s talking points from their Title II presentation refer to net neutrality as similar to “1930s common-carrier regulations that were designed for a telephone monopoly.”

But when the ISPs that are lobbying for its repeal are also required to be used in most places by government-enforced structuring (like healthcare), don’t the rules that apply to a telephone monopoly also apply to companies that are practically protected internet monopolies?

In either case, whether the Internet is free speech or privatized commodity, keep in mind the allegory of the ‘internet access package.’ It will very likely become a real phenomenon with the removal of net neutrality, which prevents (or did prevent) companies from prioritizing the data they want you to see.

*This article has been edited from the print version to correct a mistake.