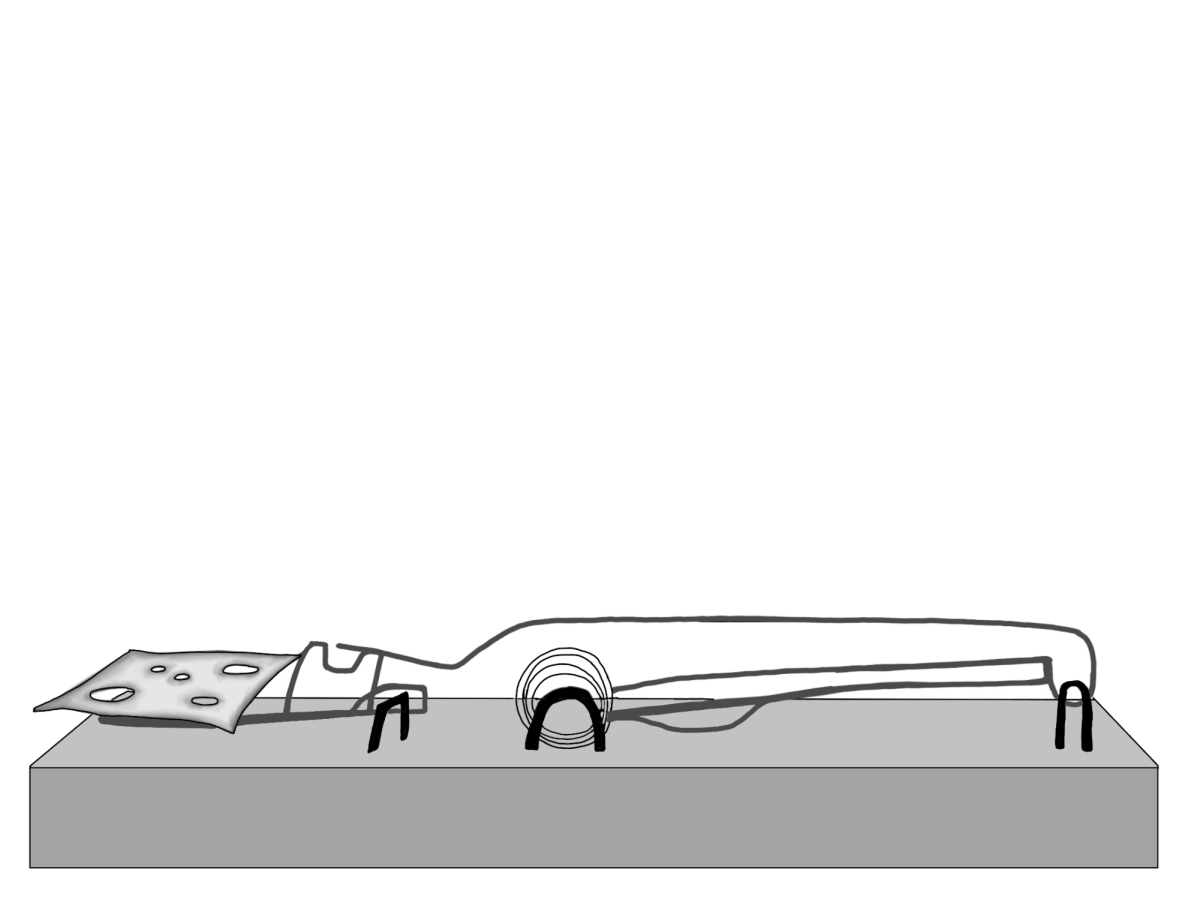

Fifty-six crafts are listed as currently critically endangered, according to the Heritage Crafts’ Red List. This list, based on the conservation status system of invasive species, determines the ability of a craft to be passed down to successive generations. To make the list, a craft requires manual dexterity and skill, traditional materials and techniques, and the ability to be passed down between generations.

Part of the loss comes from these crafts formerly being a necessity to provide for one’s family, rather than an art. Now, as machines stick designs to clothing and manufacturing is done for the masses, they’re simply no longer a necessity, and making a career as an artisan becomes an impossibility. For example, in the UK, the last framework knitter–an industry that dominated Europe in the late 1500s–retired in 2020, leaving less than 25 people who know the skill. They are also no longer taught in accessible places, as many require a skilled craftsperson to pass on skills rather than a book or video.

While many of these crafts are still viable (currently practiced and expected to be passed on to the next generation), it is more important than ever to learn and develop these art forms. My grandmother, Ellie Lida, professionally teaches basket-weaving classes, in addition to designing, weaving, and selling her own at trade shows around the Midwest. She says that “creating heritage crafts like candlemaking, preserving strawberry jam, weaving baskets, sewing, baking bread; it builds bridges between yesteryear and the present.”

Slowly, appreciation is growing. I talked to my grandmother, who taught at the Shepherds Harvest Sheep and Wool Festival in mid-May and saw a record-breaking number of people in attendance to see “something old.” She explains that “There is a deeper connection with how our grandparents did things.”

Additionally, she attributes some of the need to maintain these crafts to community. “Community builting is an integral part of attending hands-on classes and working with our hands is fulfilling and therapeutic for our soul.”

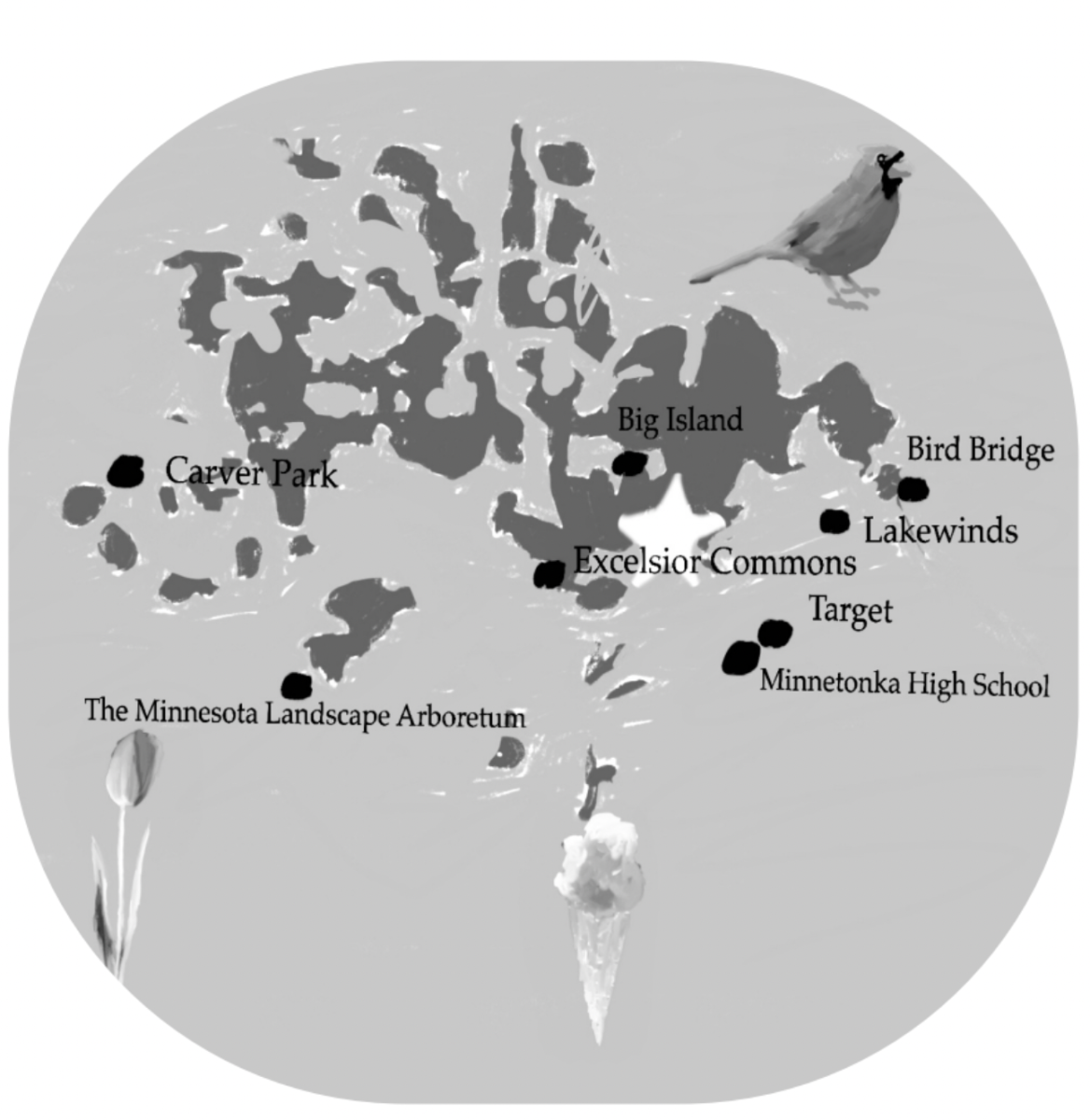

There are plenty of opportunities to develop heritage crafts. Beyond asking your own grandparents, the Minnesota Fiber Arts and Textiles Center offers classes ranging from making quilting cards to lacemaking to embroidering. North House Folk School and other folk schools across the midwest offer both online and in-person classes, covering crafts that cater to all skillsets and interests. Art and trade shows like Prairie Star Farm (9/27), FiberFest at Cambridge Fairgrounds (10/18), and Fiberfair at the Hopkins Eisenhower Center (11/1) are also excellent opportunities to experience these crafts by watching demonstrations, viewing or buying handmade wares, and hearing stories from craftspeople. There’s always something to learn.

I’ve been attending fiber fairs since I was in elementary school and have worked in several since. I get to sit in a tiny stall surrounded by baskets, shelves to highlight the most intricate designs and demonstrating weaving from a kit we designed before arriving. I walk from stall to stall to see the wares: electricity blasted bowls, dozens of skeins of dyed yarn, widdled kitchenware, sewn clothing, welded horseshoes, knitted washclothes, and hand-blown glassware.

After admiring the decades of skill it took for each vendor to hone their craft, I return to my own novice projects. Basketry is a heritage craft, passed down from my grandma to all of her children and grandchildren, and I’ve learned through careful instruction and hours spent in her workshop. I learned to embroider through kits and hundreds stitches being ripped out, only attempting to make my own design after years of working on the same canvas. Minnetonka Knitting Club taught me to work with yarn after spending six months on one project. It would take me decades to call myself a master of any of these skills, but I still love to practice them.