A High-Functioning Disaster: What I Really Learned in High School

Photo of me and my instructors after completing the Yale Young Global Scholars summer program in Politics, Law, and Economics

June 3, 2020

Here’s something I’ve learned: high-functioning does not equate to high-performing. This was a lesson that I, unfortunately, learned a little late in my high school career. As a child of an immigrant parent, I was often told stories of how difficult it was growing up during the cultural revolution in China, and how, despite the odds, my mother succeeded and went to the most prestigious university in the country. Any hope of success and social mobility rested on studying restlessly and acing the national college placement exam.

As I grew up, it was expected that I would become a star student in school, and I would go to a top university. My parents have worked tirelessly to provide me with the resources I need to succeed, and I would be terribly remiss if I ever squandered the fruits of their efforts. So naturally, I worked hard in school. I enjoyed being at school and learning with friends and getting good grades was never too difficult for me.

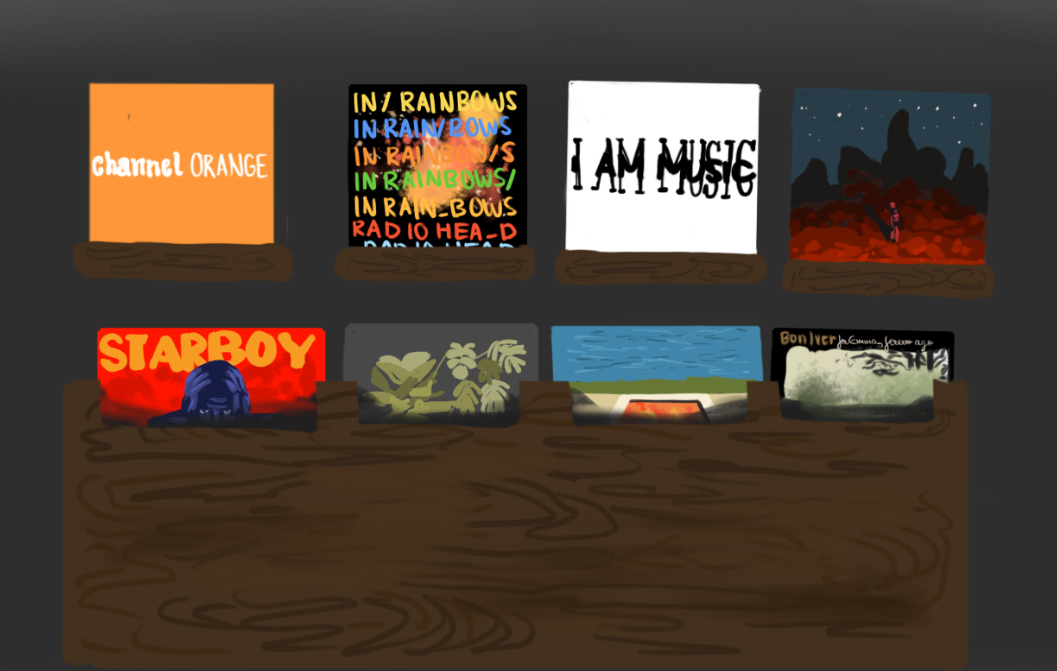

Additionally, I had always loved doing art. Be it music or visual arts, whenever I had some free time, you could probably find me sitting in some corner of my house drawing my favorite character from a cartoon show that I was watching at the time. It was a way for me to escape a bit and immerse myself in a world where the concerns of daily life didn’t follow me. As I transitioned into high school, however, I felt that I had less and less time to dedicate to the things I loved doing. People often speak of the “gifted kid burnout” phenomenon, in which students who were placed in accelerated or advanced classes in elementary or middle school often burn out by the time they reach high school and lose interest in things they once loved doing. I, unfortunately, am probably a poster child for this syndrome.

I became absorbed with getting good grades, mastering all my extracurriculars and, at the same time, maintaining some semblance of sanity. On top of that, I still had to be “well-rounded.” Why, you ask? After many sessions with my college counselor and drawn-out phone calls with parents of children who went to elite colleges, I learned that prestigious universities look kindly upon applicants who are “well-rounded” and “holistic.” I found myself questioning the value of such a requirement. To make it to my dream school, I had to spend much of my day attending class, going to music lessons, studying for the SAT, completing homework for the countless AP classes I was enrolled in–how did they expect me to have time to maintain a personality?

For the majority of my high school career, I had buried myself in the expectations that others had for me and pinpointed my focus so intensely that it quite honestly came at the cost of my mental and physical health at times, although I never let anybody see it. When I had sent in all my college applications in the beginning of senior year, I was exhausted, and I truly could not care anymore.

Luckily for me, my class workload afforded me more time to do the things I loved, especially doing art. In March, I also found out I was admitted to my dream college, and when I saw the letter of acceptance pop up on my laptop screen, I immediately broke down in tears.

These past few months, and particularly the lockdown due to COVID-19, have helped me reflect on how I “succeeded.” The truth is: I don’t really think I did. I still struggle with imposter syndrome daily, doubting how much I actually deserve to go to the university I had been working towards for so long. I wish I had found out it’s okay to take some time to do the things you love, because that time you set aside makes the time you spend doing other work that much more productive. Being a high-functioning student definitely does not equate to being a high-performing student. Overworking yourself can often do more harm than good. But above all, do what you want to do, and be really good at that! Don’t force yourself to join clubs that you don’t want to just because it will “look good” on your resume. Don’t try so hard to “make an impact” that whatever you do ends up being ingenuine. I wish I could have told 15-year-old Sophie that the road to success is not a one-way street – you have to be proactive in charting your own path and eventually tell others about your journey so that they can find their own way, too.