A Contemporary Analysis of Minnetonka’s Queer History

December 3, 2020

Notes to the reader: Towards the end of the article, there are brief mentions of suicidal thoughts, so discretion is advised.

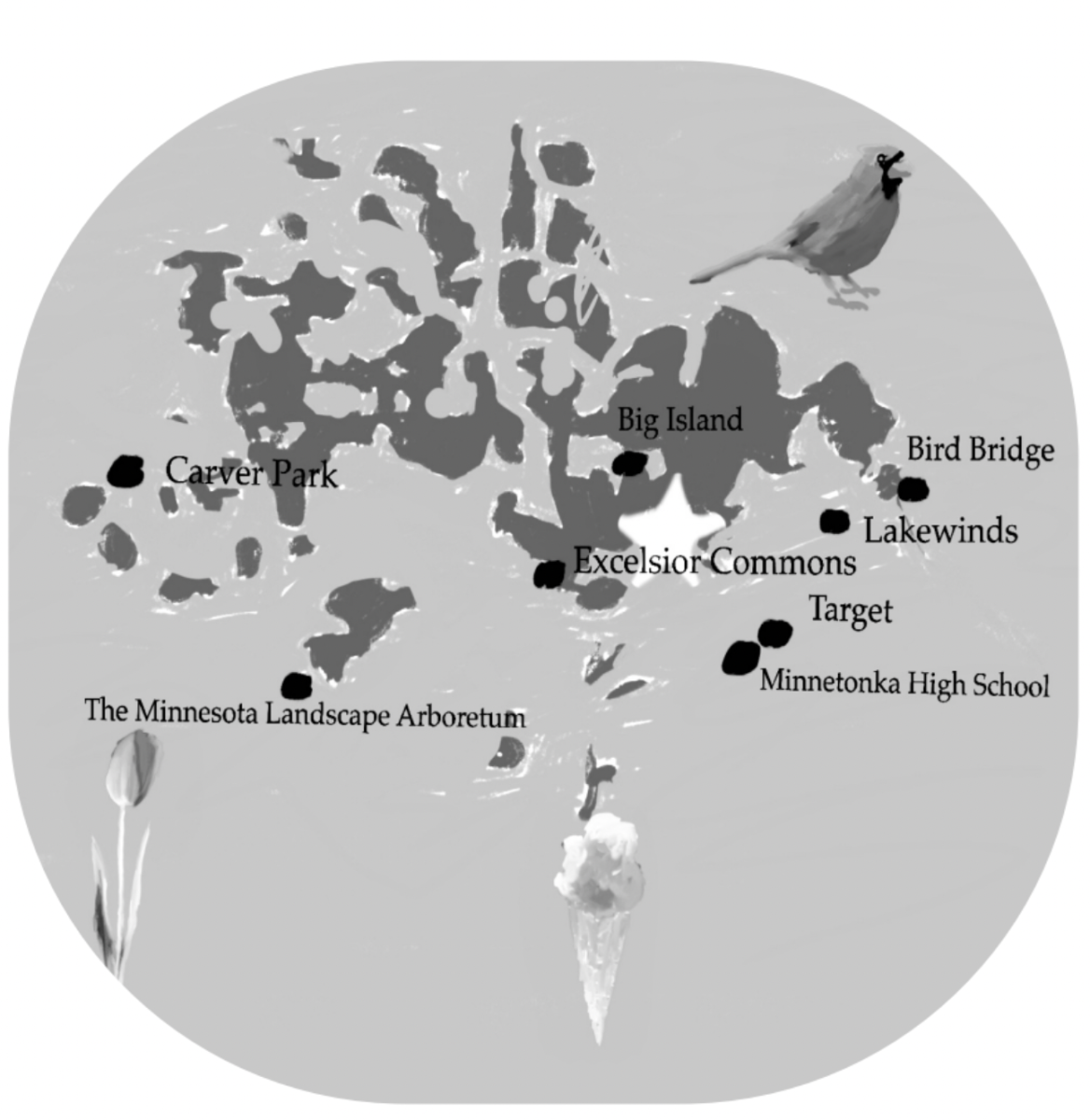

2020 has been a unique year – we’ve seen the rise of a pandemic, we’re dealing with a controversial presidential election, and we’ve seen the rise of awareness of social issues. This awareness on a national level has trickled down, affecting even the comparatively small population of the Minnetonka School District.

In a response to the recent creation of Instagram accounts that highlight the discrimination that Minnetonka students face, the Minnetonka School Board issued a press release promising to “mak[e] necessary changes” to help improve the culture and educational curriculum at the school. One of these changes was to unveil a series of goals— the most important one being School District Goal 2. Goal 2 states that the district will provide a “tireless” commitment to belonging, further defining “belong” as a “strong feeling of positive connection, acceptance and importance as a member of the Minnetonka Schools community, regardless of race, religion, gender, sexual orientation, country of origin, and socioeconomic status.”

This objective has been controversial. At the first study session after these goals were announced, six people came in to speak and all six protested it. While the outrage was over the racial issues discussed in Goal 2, it did seem that the goal itself was in jeopardy, that it might be removed from the website entirely.

At the time, I was under the impression that the School Board would, in that meeting, discuss how they would implement change, that they would take the time to discuss and rebuke some of the parent’s concerns and explain why Goal 2 was important. I even had hopes that they would talk about the curriculum and how it could change – seeing as, per school district policy 603, “The Board is accountable, in its governance capacity, for all standards and curricula”.

However, my dreams slowly started to diminish as the meeting went on. After three hours of debate over terminology, I came to the conclusion that trying to find out what the School Board would do would be ineffective, and decided instead to write about some of Minnetonka’s history instead.

And so I went, diving into the rabbit hole that is the history of queer students at Minnetonka. I interviewed people from the school’s past and the school’s present in hopes to piece together how people had been treated and what, at the end of the day, Minnetonka stood for.

Max Henke’s, ‘09, Story

Flash back to the year 2005. Ruffled skirts were all the rage, Mr. Brightside was winning MTV awards, and President George W Bush had only a year previously “call[ed] upon the Congress to promptly pass and to send to the states for ratification an amendment to our Constitution defining and protecting marriage as a union of a man and woman as husband and wife.”

Max Henke (he/him), Class of ‘09, had just begun high school. He remembered a “community of multiple opinions” and a tight and supportive friend group.

He remembered the use of discriminatory slurs in the hallways and “gay” as an insult; he also recalled the “Male-rettes” performing at Homecoming in a way that degraded drag queens and the queer community as a whole (the “Hollywood” signs from the 2008 performance played into harmful stereotypes).

Overall, Henke remembered the student body as a “wide collection of different beliefs”, a representation of both the political climate of the day and the tight-knit community of LGBTQ students and allies.

The mixed culture among the students, to some extent, reflected the culture of the staff of the school: the teachers were mostly supportive, and the administration significantly less so. Henke remembers pink triangles on the rooms of some of the teachers, including that of his social studies teacher; these triangles let LGBTQ students know they could find support there. Henke noted that not every teacher would necessarily do the same, but that the creation of these spaces was important.

In fall of 2008, as a senior, Henke applied to create a gay-straight–now known as gender-sexuality–alliance (GSA). He was met with pushback from tnen-principal Dave Adney and then-activities director John Hedstrom, who both cited concerns that the club wouldn’t be sustained, despite a number of juniors who were interested in running the club. Henke remembers Adney and Hedstrom saying Minnetonka didn’t allow political clubs at the time.

This prohibition of supposedly political clubs was actually illegal per the 1990 Supreme Court decision Westside Community Board of Education v. Mergens, which affirmed that, per the Equal Access Act, schools must provide “‘equal access’ to students who wish to meet within the forum on the basis of the ‘religious, political, philosophical, or other content’ of the speech at such meetings”.

This meant that the school was violating federal law by not allowing a GSA club to form on its grounds. On top of that, there had already been a previously established GSA club that had died off by the time Henke entered MHS in 2005.

Henke also noted the skewed curriculum at Minnetonka, especially within the health classes. While he didn’t remember anything blatantly homophobic in any of the lessons, he noted that there was a clear lack of information regarding LGBTQ people. This pattern, he continued, was echoed through other subjects.

While not explicitly homophobic in any regard, the books taught in English class had no queer characters, and the gay liberation movement wasn’t taught in any of his social studies classes. This isn’t to say that the English, Social Studies, or Health departments were explicitly homophobic – again, the teachers would often be supportive and some even helped him edit his college essays about his coming out process – but the approved curriculum lacked in creating space for these topics.

And there ended Henke’s experience at Minnetonka – an experience marked by the support of friends against a wider, less sympathetic curriculum and admin.

Sam Greenstein’s, ‘15, Story

Sam Greenstein’s (they/them) story starts directly after Henke’s–they entered high school in 2010 (the year the first iPad was sold, and the year that Usher lamented falling in love…again), and Greenstein graduated in 2015. Their graduation was in the same month as the Obergefell v. Hodges decision–the Supreme Court decision that legalized gay marriage nationwide. They wrote for Breezes and offered humorous political takes on everything from Erik Paulsen’s record to dishonest election advertising and the Pledge of Allegiance. As a journalist, they were aware of the political and social climate surrounding the school, as well as the educational climate within it.

As Greenstein grew older, they remember ill-informed health classes, especially when it came to the topic of gender and sexuality. They remembered that in middle school all health classes were abstinence-only, and high school wasn’t much better. Classes covered some topics related to dating, but everything was exclusively heterosexual. This left wide gaps in Greenstein’s education–school wasn’t able to teach them how to label themself, which was a struggle their cisgender and hetrosexual peers never had to go through.

Greenstein’s English and social studies classes didn’t have much to offer on this subject either–they don’t remember any lessons on the gay liberation movement in social studies or any LGBTQ characters in any of the books they read. Though the GSA was established again in 2010, their identity was not represented in the curriculum.

“I didn’t experience explicit homophobia in high school,” they stated, “but there were no LGBT mentors […] there were adults I knew were supportive, I knew I had different teachers [who were supportive] in high school, but there were no out teachers to serve as positive role models”.

They recalled a culture where not everyone was completely comfortable with being out, which in turn took a serious toll on the mental health of their LGBTQ friends. Greenstein remembered friends who had attempted suicide because of the lack of understanding and acceptance of their identities. Greenstein’s outgoing, remarkable character was stifled while they were at Minnetonka, and the school culture had an even more tragic impact on their companions around them.

My, ‘22, story

Flashforward to today. There’s all kinds of music on the radio and a good chance Obergefell v. Hodges could be overturned by the Supreme Court. Classes are online, and we’re all struggling at home–some of us have families who accept our identities, and some of us do not have that luxury.

In either 6th or 7th grade, I (she/her) had to write a small three-paragraph page on my ideal partner for health class. I can remember my pre-teen self struggling with the wording of the essay, but there was exactly one word I knew was correct for my future partner: the pronoun “they,” not “he.” For all the time I spent looking in a thesaurus for ways to reiterate my points, I didn’t question the use of the word “they.” At the time, I was aware I liked girls, but I didn’t have the vocabulary to describe it–I knew of “gay,” and I knew of “straight,” but I wasn’t clearly either of those (hence, the gender-unspecified pronoun to refer to my future partner).

When it came time to get a required parental signature, I can remember my mother questioning me about my choice in wording. Without knowing the vocabulary that could even describe me, I was unable to really express that I fell under the bisexual umbrella, and I felt lost trying to justify my own emotions. Despite my use of ‘they/them’ pronouns to identify my future partner, the essay I turned in used ‘he/him’ pronouns throughout – a result of not being taught a non-heteronormative vocabulary for describing my identity in school.

It was not until 9th grade, a number of years removed from the health assignment and a year after I started dating a girl, that I finally had the courage to come out to my parents. It went a lot better than the first time I tried, and I’m incredibly thankful for that and for the fact that I have parents who didn’t try to send me to conversion therapy or berate me in front of the church. But that doesn’t make what I went through in middle school any less real, and it doesn’t change the fact that I felt genuinely defenseless trying to describe what I was, lost in a way that my peers just weren’t.

I recognize that I’ve been lucky in this. I know of people who have attempted suicide because of the homophobia they’ve faced at Minnetonka. I know people who have had their families insinuate they’d be indifferent to the death of their queer child, and who were not able to find support in Minnetonka’s staff. I know people who have been bullied and beat up because it was suspected that they were gay. I know people who used to wake up and not want to go to school because they didn’t want to face everything Minnetonka presented to them.

The Story of the Future

This isn’t to say everything at Minnetonka is bad. As our school’s web page highlights, we have some of the nation’s highest standardized test scores. We’re recognized as the best public school in Minnesota by Niche.com. We have an amazing set of teachers who are, at least in my experience, all very supportive of their queer students.

Furthermore, Principal Jeff Erickson has made a point of meeting with students who have expressed concerns, going headfirst into the issue of “how do we support all students and how do we make sure every student feels included?”.

He recognizes that “we need to make sure students feel that there are multiple voices in the work we are doing”, and humbly noted that “the best feedback I’ve gotten over my time as principal has come from students who have met with me”.

It cannot be ignored, however, that the culture at Minnetonka that is so often bragged about is one that doesn’t always protect its students. As much as the teachers want to support the students, that doesn’t change the fact that our district’s approved curriculum leaves out information LGBTQ students desperately need and rightfully deserve.

In recent years, there have been efforts to try to change this. One of the main organizations participating is the Minnetonka Coalition for Equitable Education (MCEE). They have staged protests and made efforts to engage with the Minnetonka School Board to try to change the approach to curriculum in the school district. I highly encourage that people check out their Instagram account and the important work that they have done.

The MCEE is comprised of people who have experienced firsthand what Minnetonka is like and, moreover, have made an effort to change it. They lead marches attended by people who are aware the situation needs to change, aware that the curriculum must be more accurate to the population and that the environment needs to protect the students.

But this work cannot come into fruition on the work of one organization alone. I write this not to write directly to the school board, but to the community, to the people who could be marching. There have historically been problems at Minnetonka, but they can be corrected if people are held to account.

And people can only be held to account if the community is aware enough, and cares enough, to do so.