America’s Top Pop Stars: Do They Have The Right To Copyright Sound?

February 14, 2020

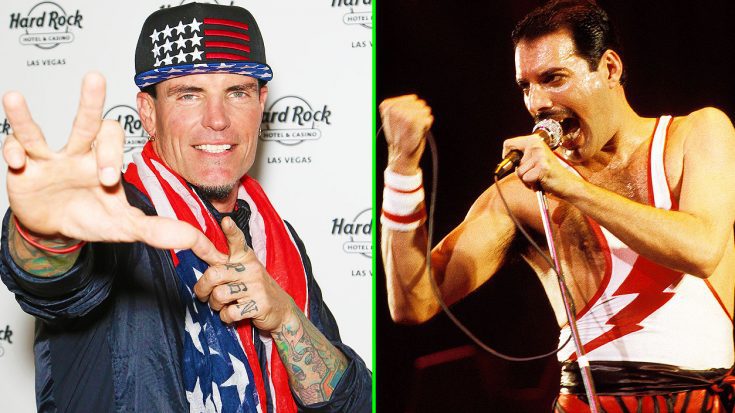

The concepts of copyright and plagiarism in music have always been relatively controversial. For example, Vanilla Ice had to settle a court case over the remarkable similarities between the bass line of his song “Ice Ice Baby” and “Under Pressure” by Queen. However, despite many high profile court cases, the question still remains: how much of a song can one really own?

The law itself is rather confusing. It outlines two distinct rights: the right to one’s musical work, or the song itself, and the right to one’s recording of the song. Generally speaking, the publisher of one’s music often owns the copyright of the musical work, while the copyright of the recording belongs to a record company. Music can only be copyrighted if it is considered an original work and if there can be a tangible record of it. A tangible record can be sheet music, a MIDI file, or a recording. In simple terms, as soon as an original song is written out as sheet music or recorded, it is copyrighted. Oddly enough, it is not required that one register the song at the US Copyright Office.

The biggest problem with the law is that it relies heavily on the opinion of the court. There are a few general rules, but not all are upheld. The court holds that the song must be original, but the definition of original is flimsy. The song must be the artist’s own creation, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be something novel. In the case of Vanilla Ice vs. Queen, Queen’s copyright held because the bass line was their own original creation. However, many courts uphold that rhythm and harmony are not original and are therefore public domain.

Despite all of this confusion, and samples have yet to be included in the mix; they cannot be found on the site for Copyright Registration for Musical Compositions. The general rule appears to be that one must credit the artist responsible for the sample in order to avoid being sued.

So how does copyright work when it comes to lyrics? Most courts dictate that while one can copyright the overall lyrics of one’s own song, they cannot copyright phrases unless they are entirely original. For example, “Happy Birthday” cannot be copyrighted because its origin is disputed. However, there do appear to be exceptions to this rule.

In 2014, Taylor Swift successfully trademarked the phrases “party like it’s 1989,” “cause we never go out of style,”“could show you incredible things,” and “nice to meet you, where you been?” She also trademarked the phrase “this sick beat.” One could argue that many of these phrases are not original, but their copyright is upheld by the US government. Oddly enough, another one of her songs, “Shake It Off,” has been accused of copyright infringement over the phrase “haters gonna hate, players gonna play.” As of 2018, the courts had decided that the phrase was not original, but a successful appeal was made in 2019. The case has not yet ended.

Another more recent case is Ariana Grande’s “7 Rings.” She’s been accused of copyright infringement by DOT, a rapper who’s song “I Got It” is remarkably similar in musical composition. Grande’s song also uses the melody of the song “My Favorite Things” from The Sound of Music.

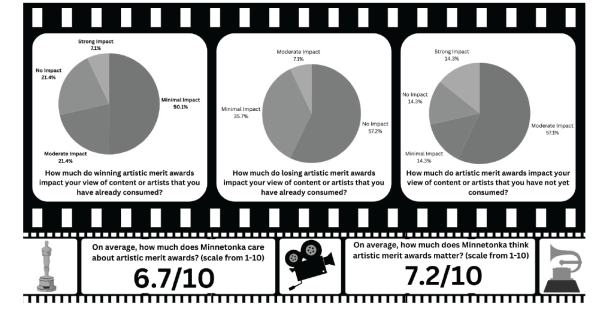

Since it’s not quite clear where the law stands, one has to wonder where the students of MHS do. Here are the responses of students when asked whether artists should have the right to copyright small parts of their songs like phrases, rhythms, harmonies, or melodies.

Madison Andrews, ‘22, was conflicted. “That’s hard,” she said, “because some of the phrases and bass lines are really similar. I want to say yes because it’s their [work] and they can do what they want, but that’s also really difficult to do.”

Elise Pudwill, ‘23, thought that there are “lots of phrases, rhythms, basic melodies, and harmonies that are very commonly used.”

Pudwill believed that it would make little sense to copyright them. However, she did note that “it can stifle creativity if an artist has to check if a couple [of] measures have the same melody as another song.”

Claire Dolan, ‘23, had a slightly different take on things. She doesn’t think that artists should be able to copyright small things. Dolan said that “there are so many songs out there and the number will just keep increasing. Eventually there is going to be some overlap and that’s okay. If artists would copyright small things, every song would be a lawsuit waiting to happen.”

Dolan does believe that musicians should be able to copyright their own music, but she said that she “guess[es] that it shouldn’t be as strict as other copyrights.” According to her, “a lot of times in history, and even in the modern day, up and coming artists will write a song and a more popular musician will steal it.”

Dolan doesn’t find this fair but is uncertain where the line should be drawn. She has no doubt that there needs to be some regulation.

Both Andrews and Pudwill also agree that artists have the right to copyright their own music. Andrews said that “They’re the ones that created the material and it’s original, so technically they have the rights to their own creation. It’s kind of like owning something as a possession; you have rights to it and no one else.”

While the question of who can own how much of the composition of a song still remains up in the air, one can admit that it sparks plenty of important conversation. Perhaps it will take a few more high profile cases for the question to be resolved, or perhaps it will go to court every time. Either way, it does not appear to be an easy question to answer.