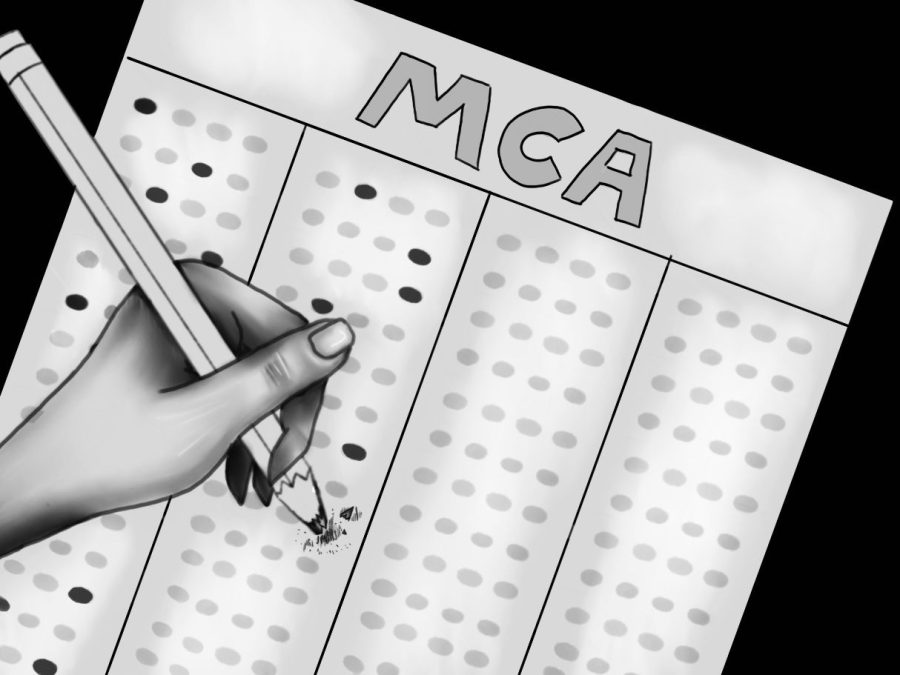

Are The MCAs Actually Beneficial, Or Just An Annoying Chore?

April 29, 2022

With another standardized test having come and gone and the end of the school year fast approaching, this is the season to examine the utility of tests like the MCA, as well as standardized tests in general.

The Minnesota Comprehensive Assessment (MCA) is a test administered by the Minnesota Department of Education (MNDE) over various fields of study – reading, math, and science – to “evaluate equitable implementation of the standards in schools and districts across the state.”

Since the exam is designed around measuring how different districts meet the academic standards set by the state, students’ test scores reflect Minnetonka High School generally, not individual students. This system stands in contrast to other exams that MHS students might be more familiar with, such as the AP, IB and ACT tests, where students are more directly compared.

Higher Algebra and Precalculus teacher Kate Ohrt praised the aim of the test and said that the MCAs can be, “a really good gauge of where we’re at as a district,” and that they can be especially useful in “[comparing] us against our counterparts.”

When the MNDE receives a district’s MCA scores from across the state, it can use them to make sure the state’s academic standards are still effective, as well as to record and address academic inequalities between districts. For instance, the significant drop in MCA scores between 2019 and 2021 (there was no MCA in 2020 due to the pandemic) shows the impact that COVID-19 has had on teachers’ ability to teach and students’ ability to learn.

However, this universal application often obscures the nuances of context. Take the consistent underperformance of poorer districts on the MCAs, for example, particularly urban ones with more students of color. Observing the scores alone, one might falsely interpret students of color to be less intelligent than their white counterparts, an incorrect and dangerous conclusion used to defend bigoted behavior. However, when one examines the broader societal forces and complex conditions at play, it becomes clear that this underperformance is due mainly to systemic racism and poverty. Even beyond that, the simple fact is that many, if not most students, do not learn and utilize knowledge in the way standardized tests demand.

At MHS, the atmosphere with respect to standardized tests like the MCA seems to be one of annoyed exhaustion.

Annika Sanschagrin, ‘24, said that her former math teacher “[hated MCAs] as a student and [hated] them as a teacher.” Sanschagrin herself said that she did not enjoy taking the test either.

Still, both Sanschagrin and Ohrt admitted that they found the MCA preferable to other tests typically taken by Minnetonka students. In particular, Ohrt commented on how the MCAs do not have a time limit and allow students much more flexibility than other exams.

“When you have all the time in the world you can fully think through the question and answer it to the best of your ability without overexerting yourself, versus an ACT where you would be encouraged to guess,” Ohrt said.

The MCAs also manage to avoid the pitfalls of courses that tend to “teach to the test” since the MCAs are themselves derived from prescribed state academic standards.

Still, Ohrt conceded that “at the end of the day it’s still a standardized test,” and Sanschagrin echoed this sentiment. Speaking of her own courses, Ohrt said, “I want every kid to like math—but if the MCA then becomes a stressor, it handicaps me as a teacher to help that kid love math.”